A few months ago, we kicked off our multi-benefits partnership work with The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and Code for America (CfA). The partnership aims to improve the social safety net in the country, with a focus on making programs like health insurance and food assistance easier for residents to access and states to maintain, even as the rules that govern these services change.

We’re building on work started by USDS and CMS in 2016 and are beginning to explore the realities of making change to an enormously complicated system. We know that there is no shortage of opportunities to improve the delivery of social services in the US. We’re visiting communities across the country to understand the experiences of people who rely on and manage the social safety net everyday.

These conversations are showing us where there are opportunities to try out new processes and tools, all in service of getting people the help that they need, faster. By the end of 2018, our goal is to put forward the first draft of a set of gold standard, modern tools that any state or program can incorporate into their eligibility and enrollment system and in doing so deliver an experience that is measurably better for clients, caseworkers, and agency leaders.

Delivering on this mandate will require a lot of work and we’ve only just begun. Over the last few months, we’ve started conversations with five states and begun field research with two states to learn more about the day-to-day realities of state leaders, caseworkers, and the people they serve.

What we're looking for

Improving the social safety net is hardly a new idea. Many states are already undertaking what are called “modernization” initiatives. Most of these projects will take advantage of federal funding to bring newer technologies to the tools that states use to sign people up for safety net programs. Given that these efforts are already underway in some states, there are opportunities to help other states learn from that work. Conversely, diving into current innovation projects illuminates the accepted standard and challenges us to try to raise it.

Our primary research question: Where are the best opportunities for dramatic gains in the quality of the social safety net?

To answer this question, we need a full view of the safety net ecosystem in the US. We need to understand the people involved at every step, from residents all the way through to the state leaders accountable for the integrity of the system. The best way to get started? Actually meet them, face-to-face. We went to the field and asked these folks about their day-to-day work, their biggest worries, and their vision for the future.

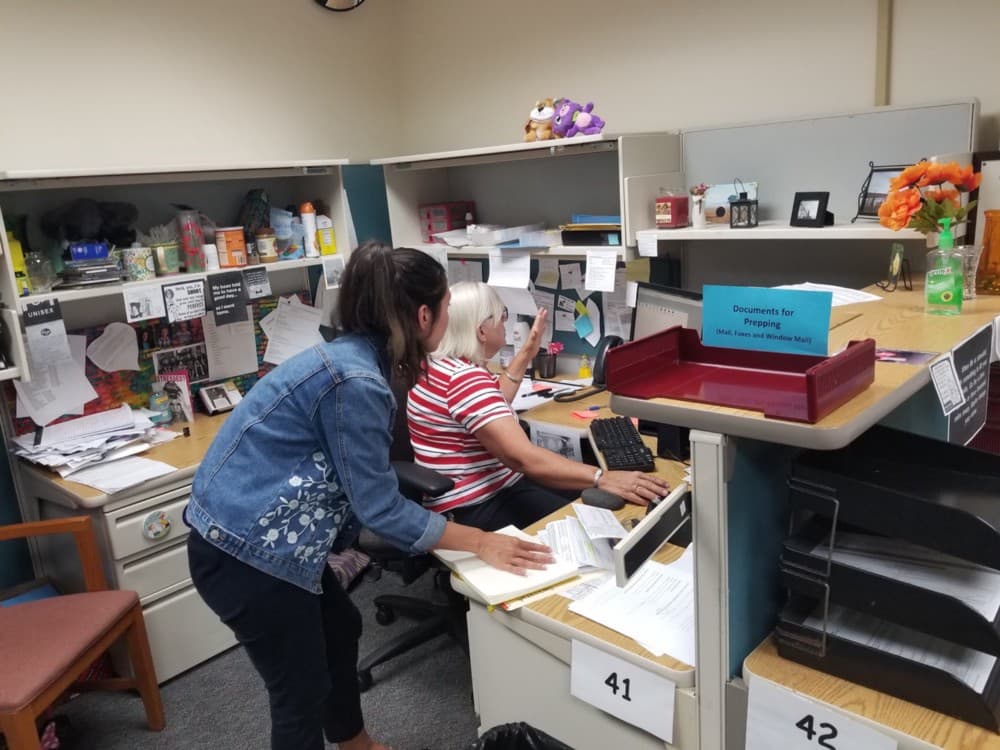

The Benefits Partnership team learning about social service delivery in Michigan.

What we've heard so far

The challenges faced along the path to delivering social services manifest in various, but connected, ways, at every stage of the process. When a state leader tries to build a safety net program that is both compliant and modern, there are cascading implications for both staff on the ground and the people who rely on those services.

One illustration of the different perspectives involved in delivering benefits might look something like this:

Residents: We’ve heard that their experience can vary wildly, with some of the most vulnerable residents, like immigrants and the very sick, reporting a cumbersome, slow experience. One resident applying for social services said, "Back in April, she said I had everything I needed. You told me everything was fine. Now I need to apply again?"

Caseworkers: Caseworkers report being over capacity, sometimes managing a caseload in the hundreds, often with technology that seems to work against, rather than with, them. One caseworker said, "You just need to learn exactly how it works — then it’s easy."

Observing field offices helps us understand how the social safety net functions day-to-day.

Program leadership: Program staff and leaders share stories about being overburdened with little visibility into how their work impacts residents. One program director shared, “We don’t have a great way to track outcomes. Does having a better application actually make people any healthier?”

Technical teams: Technical leadership report being tied to outdated legacy systems that make it difficult to iterate or even adjust to changes in policy. One leader shared that issues migrating historical data (which by law, they must keep) from a mainframe legacy system was holding up the state’s modernization efforts, adding “We have that data in there, but have no idea how to get it out.”

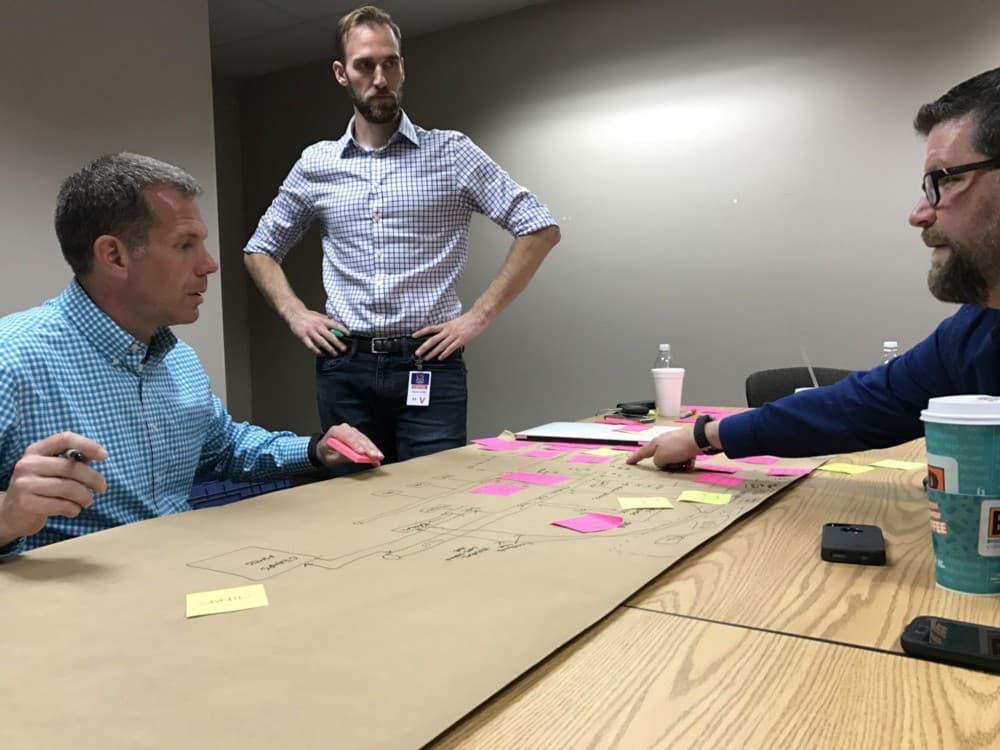

Collaborative workshops help us understand the realities of technical architecture and where states have found opportunities to innovate.

State Leadership: State leaders are accountable for the entire system, people and technology included. We’ve heard stories of bewilderingly complicated policies, which are seemingly handed to state leaders without clear implementation guidance, and public failures, which leave teams wary of taking on new initiatives. As one office supervisor said, "It’s not possible to design an application that someone could complete in a day."

As residents, many of the complexities that we observe when we interact with government services seem to have a direct solution — a quick fix to make a line move faster or a question easier to answer. But what we’re seeing in our research, and still synthesizing for ourselves, is an interwoven ecosystem defined by the constraints of important laws, policies, and business processes, all designed to protect taxpayer funds. We’re also seeing how this web we’ve built together is testing the capacities of the people maintaining and working within it. One can imagine how easily well-meaning choices by people at each of these steps could lead to a confusing experience, with many wrong doors along a complicated path.

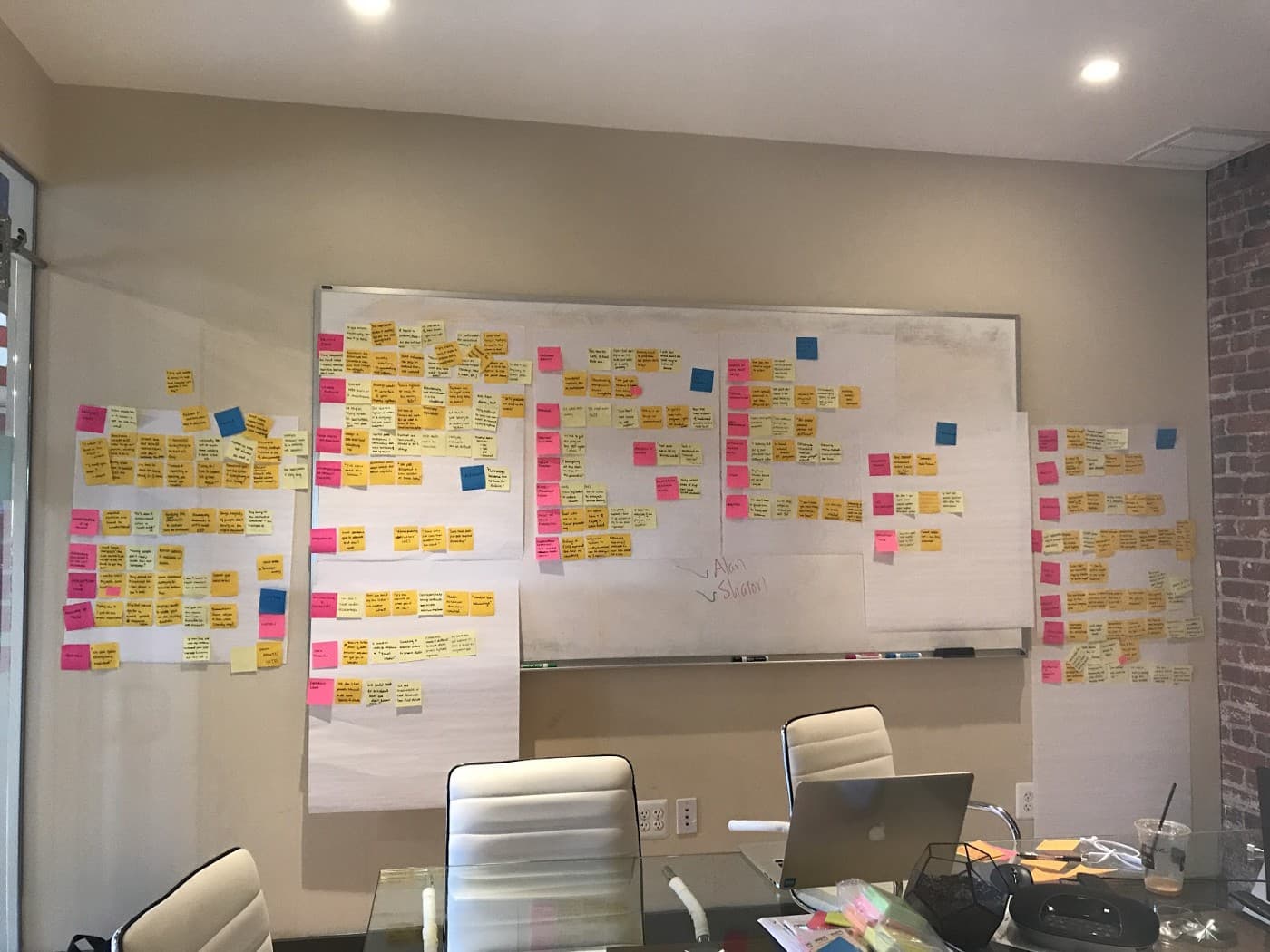

Our researchers’ nth attempt at trying to organize the levels of complexity we’ve observed.

We’ve also seen examples of state leaders innovating within law and policy to improve services and we’re excited to help other states benefit from those wins. Most crucially, almost everyone we talk to wants better processes, better tools, and better outcomes for residents — but report that their hands are tied when it comes to enacting deep, meaningful change.

Why this matters

There are shared challenges across states when it comes to delivering a modern social safety net. Our major hypothesis is that, despite differences in political context, and the particular progress states have made to modernize, building a modern social safety net will take states down a common path and we can provide tools to help them along.

For this work, finding common challenges also means finding common opportunities. Instead of a process where a state needs a service, buys it, and alone enjoys the benefit of that service, their investment should also benefit other states. We’ve structured our work to take as much risk as possible out of those investments — starting small and running experimental pilots with the aim of making it dramatically easier for residents to access and for states to maintain their social safety net.

What comes next

We’ve only visited two states so far and are deep in our initial synthesis. We’re developing ways to share our research so that it grows as we visit new states and keeps our learnings open to others who want to contribute. In the next few months we’ll be selecting and kicking off 3–5 experimental pilot projects and, by the end of 2018, will have a first version of a gold-standard toolkit available for all states. We’ve got a lot of work ahead of us, and we’ve only just begun.

Written by

Director of Design