Nava partnered with the United States Digital Service (U.S. Digital Service), the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and TISTA Science & Technology Corporation (TISTA) to improve the benefit appeals process for Veterans. Together we designed a set of digital tools called Caseflow. Caseflow has made it possible for attorneys, judges, and administrative staff across VA to process appeals and serve Veterans more quickly, efficiently, and effectively. Along the way, we also helped update a decades-old policy.

Approach

Using modern, human-centered design practices like user research, prototyping, testing, and mapping, we identified and solved for the big picture—which included but wasn’t limited to technological issues. Addressing the system holistically allowed us to design and build services that were both human-centered and built with the best technical practices.

Outcomes

We not only designed and built a set of digital tools called Caseflow but also helped change an 85-year old policy. Now:

Fewer than five percent of cases processed with Caseflow Certification have data problems. Before, 41 percent of cases arriving at the Board of Veteran Appeals from regional offices had missing documents and 30 percent had data discrepancies.

The requirement to fill out Form 8—which we identified as a redundant and time-consuming source of data discrepancies—has been removed from regulations.

In total, modernization efforts have reduced the backlog of Veterans waiting for an appeal by 50% in about one year.

As a result, Veterans and the civil servants who process their appeals for benefits get a more transparent and timely experience.

Caseflow was also recognized with a 2020 FedHealthIT Innovation Award.

Process

Seeing, testing, and evolving policy

Esteemed designer and educator Liz Danzico calls interaction design “the exploration of recently possible futures.” In government, you could say service design is the illumination of policy futures.

Because policy change is a long, winding, and often circuitous route from written law to the implementation of that law, it’s not always easy to see what it will look like in practice.

But laws and policies shouldn't, in the words of UK's Government Digital Service co-founder Tom Loosemore, be "500 pages of untested assumptions." We should be able to see, test, and evolve policy to best meet the needs of people.

As Code for America's founder, Jennifer Pahlka says, "in the digital age, we have the ability to give the 'pilots' of our government programs the necessary instrumentation to see where they’re headed and course-correct along the way."

"Necessary instrumentation" includes modern practices like aligning on clear outcomes with your stakeholders, user research, prototyping, testing, and mapping. These tools can help shape policies to better match the needs of those they aim to serve. They’re especially useful when the goal is unclear or undefined because they help illuminate a variety of possibilities and build a case for the best one.

Discovering the sources of VA’s challenges

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs employs nearly 380,000 people who provide care and administer benefits to 21 million Veterans. The Board of Veterans’ Appeals (or The Board for short) and its appeals process were created in 1933 so Veterans could appeal decisions made about their benefits, such as healthcare, financial assistance for education, etc.

In the 85 years since, policies and technologies have changed, yet the tools civil servants have to complete digital and manual processes are not often integrated or seamless, making the system large and complicated. It's worth noting that The Board is not alone; for many reasons, government agencies struggle to adapt to the digital age.

Today, attorneys and judges at The Board decide whether to grant benefits appeals from Veterans from all U.S. States and territories. The process can be straightforward, but if any changes are made to a case along the way, errors exacerbated by manual data entry and inflexible, disconnected legacy technology systems, have the potential to derail and delay a case, creating a poor experience for the Veteran.

As a result, 400,000 Veterans face years-long delays to receive a decision on their appeal. About 7.5 percent wait up to ten years. And three percent of Veterans die while awaiting a decision on their disability claim appeal.

Not just solving technical problems

Technology modernization can help foster systemic change. While our team was tasked with reshaping the information systems and digital tools that powered the appeals process, we saw that the problems that needed to be solved weren’t solely technical. Before Nava joined the project, our colleagues from U.S. Digital Service aligned with the VA Board partners and stakeholders to collectively draft a mission statement with three clear, agreed upon outcomes:

Empower Board employees with technology to increase timely, accurate appeals decisions and improve the Veteran experience.

Agreeing on these outcomes gave us room to step away from approaches that updated technology but did not improve Veteran or VA employee outcomes. It gave us space and permission to research, prototype, and iterate our way to services which were both human-centered and built with the best technical practices.

Updating an 85-year-old policy with a prototype

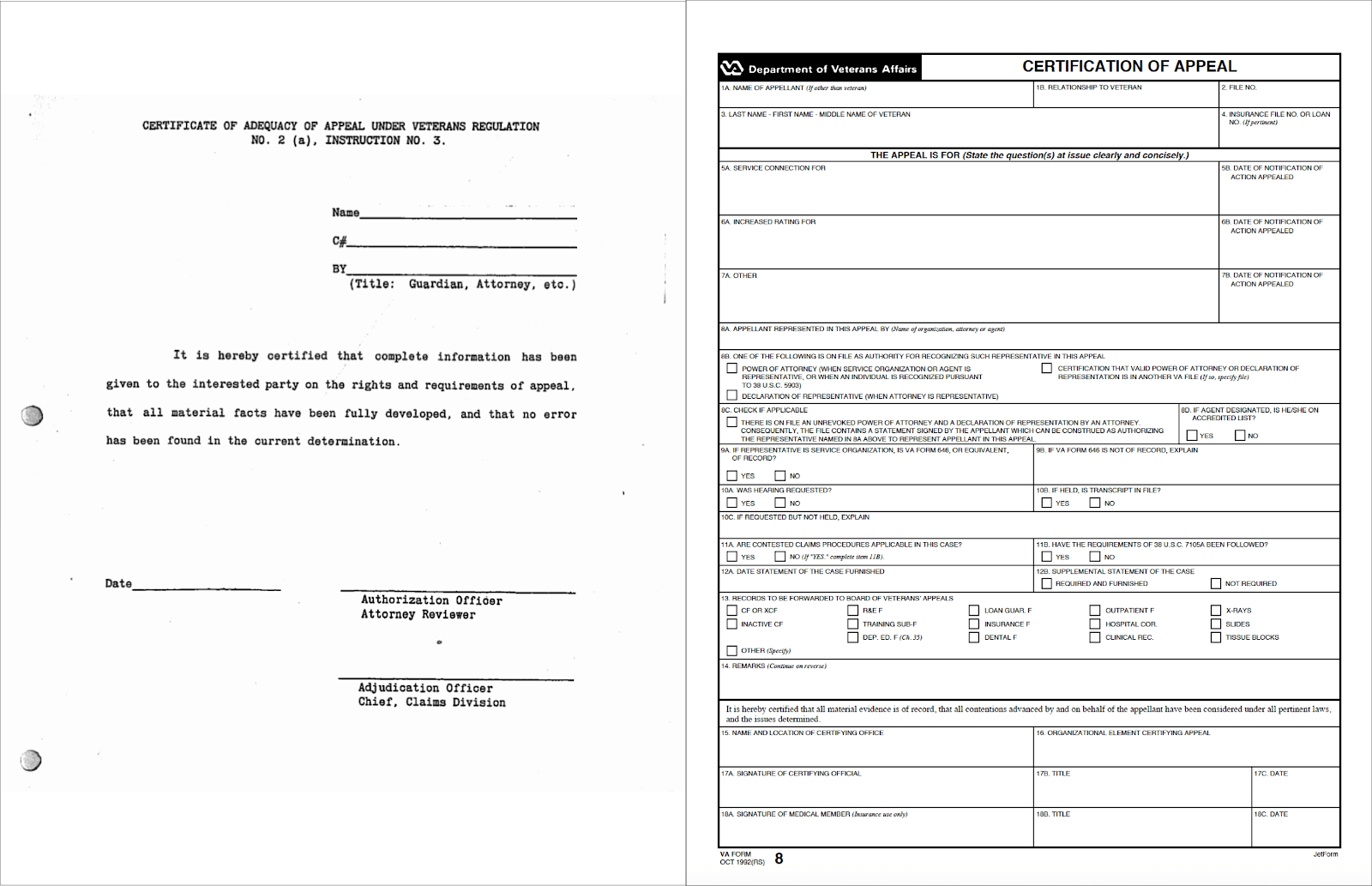

The Caseflow team began with a research phase during which we observed significant instances of delays and inaccurate data in the appeals process: the points where paperwork was transferred from one VA organization to another. For example, we found that 41 percent of cases arriving at the Board of Veteran Appeals from the regional offices had missing documents. And about 30 percent of cases had data discrepancies that caused delays. Upon looking more closely, we found that to transfer cases between the two organizations, VA staff had to manually fill out a form, Form 8, to verify that the case had been reviewed as it passed from one organization to another.

Form 8, first created in 1933, was then a simple three-step form to document that a case had been reviewed. But after 85 years of patching on additional data points and check boxes, the form had expanded to multiple pages and required a significant amount of time to fill out.

On the left is Form 8, as it originally appeared in 1933. On the right is Form 8, circa 2017. Both images courtesy of VA.

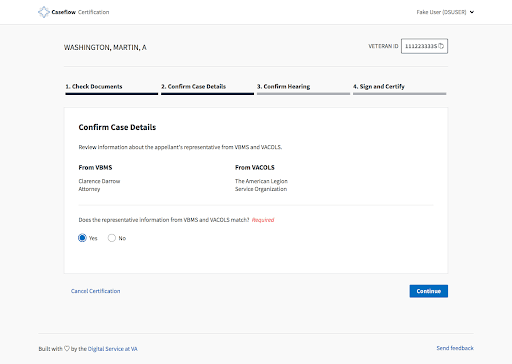

After learning from the research, the Caseflow team prototyped and built Caseflow Certification, a tool that checks for missing documents and fills out a digital Form 8 to save staff time. After it launched, the missing document rate dropped from 40 percent to 2 percent, but the data discrepancy rate remained just as high as before. We had more work to do.

Form 8 as it appeared on an early version Caseflow Certification, circa 2017.

We went back to interview the VA staff at the regional offices and The Board to better understand their workflow, where we heard repeatedly that while filling out Form 8 was a required step, information gathered in this form existed elsewhere, and no one relied on the form to do their work. Instead, VA staff manually corroborated data discrepancies between two legacy systems that contained Veteran information and documents, each siloed within its respective VA organization.

On learning this, we quickly designed a prototype that demonstrated to our stakeholders:

Removing Form 8 would ease the manual burden of data corroboration. We learned this was feasible in our research, which revealed no one needed the information on the form.

What we build could automatically surface data discrepancies to the staff, allowing them to focus their time on remedying errors rather than scouring all line items on Form 8. In other words, The Board was able to meet regulation and policy requirements by filling out the fields of the Form in the background, but staff at regional offices didn't need to spend time filling it out.

In addition to helping align within the organization, the prototypes did well in our user research with staff. These were necessary steps towards achieving the two-pronged outcome that we collectively sought: reducing the missing document rate AND the data discrepancies. And it did. Now, fewer than 5 percent of cases processed with Caseflow Certification have data problems, and the requirement to fill out Form 8 has since been removed from the regulations.

Our changes to Caseflow Certification reduced data issues by surfacing to VA employees when data shared between two important VA databases didn't match.

Better understanding the people we’re serving

In the fall of 2017, while we were one year into improving the appeals process, Congress passed a major law, the Veterans Appeals Improvement and Modernization Act (AMA), which would fundamentally change the ways in which Veterans appeal for benefits by giving them new/additional choices when they disagree with a VA decision.

Congress gave VA 18 months—until February 19, 2019—to come up with a plan to implement these changes, so The Board had to speed up the original system of processing legacy appeals (in which more than 400,000 of Veterans were already waiting for a decision) while incorporating new appeal option types mandated by the AMA. When a massive law such as the AMA is passed, implementation details can be ambiguous and open to interpretation. As our government partners work diligently to translate legislation into process, we've found many opportunities to prototype and explore a variety of ideas that help our partners nimbly arrive at more informed implementation proposals.

Caseflow team members analyze feedback from Veterans after a round of research.

As part of rolling out the new legislation, VA wanted to test the receptiveness to the new options and planned a pilot to invite a group of Veterans to opt into new, uncharted appeals options. The VA planned on sending letters to about 350,000 Veterans with existing legacy appeals to describe how they could optionally switch over to new ways of requesting a review on a previous VA decision about their benefits. They could also choose not to take any action, and continue in the legacy appeals system. Our team proposed that we test these letter drafts with real Veterans, before mailing them out. Getting feedback from Veterans would help policymakers understand how letter content affects a Veteran's understanding of the new options, and therefore the choices that they will make. In fewer than 10 days, we'd spoken to Veterans and documented improvements to the letter based on their feedback. Our scrappy research and testing sprint, and the resulting insights were well received and implemented by our government partners.

Xena Ni sets up a bespoke screen-sharing configuration for a remote usability session. Photo courtesy of Caseflow team member Annie Nguyen.

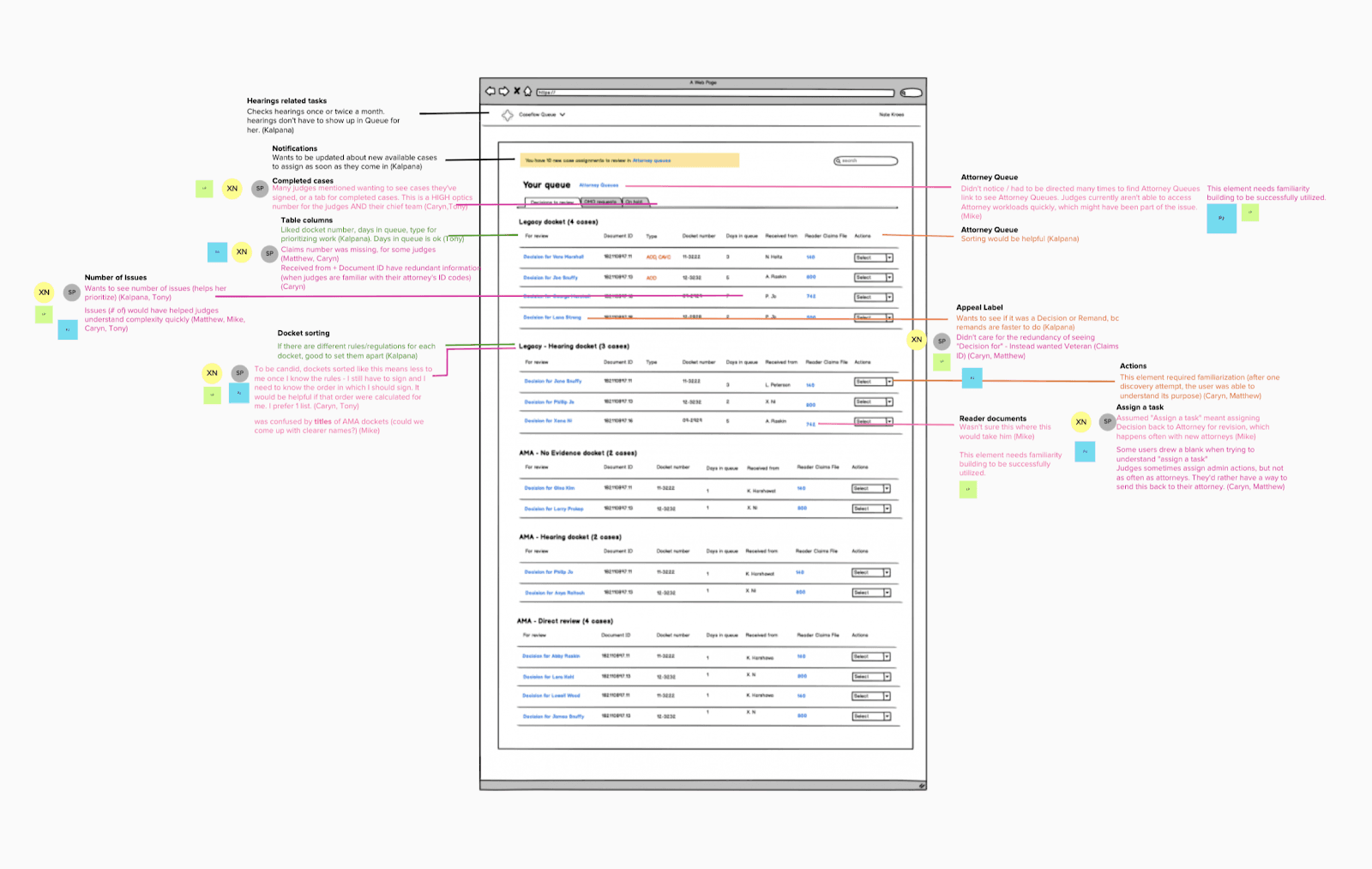

Prototyping to show possibilities

As part of modernizing the appeals process, our team is building a service that will help Board staff view, manage, and transfer their cases in an easy way. We started to integrate the new law's intended guidelines into our early prototypes so judges and attorneys at the Board could see and react to how working appeals from both systems at the same time would feel like in practice. This gave them the early opportunity to comment on what made sense and what didn't. By taking their feedback into consideration, we were able to explore a variety of ideas and arrive at an experience that matched both their needs and the legislation's needs. This fed well into our agile process because engineers were able to do accurate sprint planning on the well-vetted design that they'd been observing in use and iterating with us.

Prototyping, usability testing, and post-usability synthesis helped us explore and evaluate how judges may want to view mixed dockets of cases.

Preparing for the unpredictable future

The practices we've outlined—aligning on a product vision, doing user research, and delivering early prototypes—should help anyone drafting, implementing, or changing policy to respond faster to the needs of people affected, and lead to better outcomes that deliver on an agency's mission. In our continued work, we show our teammates and our government partners possible implementations and consequences of policy decisions. We prototype and test ideas with Veterans who tell us what's working and what's not. This makes regulations and procedures tangible, giving voice to thousands of VA staff and millions of Veterans so that they can help shape the services and tools created on their behalf.

What if policy implementation made systems more whole, instead of more fragmented and silo-ed? What if it was standard practice to prototype the consequences of the policies as they’re written by policymakers? What if every public service could be thoughtfully and quickly tested before being launched? What if policymakers were versed in prototyping and testing, or came from design backgrounds? The more clearly and vividly you can imagine possible futures, the easier you can plan for them.

Additional resources:

Delivery-driven Government by Jennifer Pahlka

Taking the Guesswork out of Policy by Tom Loosemore

Hundreds of Thousands of Veterans’ Appeals Dragged Out by Huge Backlog by Ben Kesling

Product management in government: It’s essential when the stakes are high by Ivana Ng

Special thanks

Special thanks to Nicholas Holtz, Digital Services Expert at United States Digital Service, for his input on this case study. Much appreciation to present and past members of the Caseflow team and our dedicated collaborators at the Department of Veteran Affairs. Many hands made light the work behind Caseflow Certification, removing Form 8, and implementing new legislation.

Written by

Design Lead

Director of Design