States across the country are investing in technology that streamlines access to critical services such as food, medical care, and childcare. As they approach designing technology for public services, it’s crucial that states collaborate with people who are eligible for and currently utilize the service; community members who inform and assist others in applying for the service; and the civil servants who administer the service.

At Nava, we believe that human-centered design and agile development are essential practices to deploy when building public services. Both of these practices rely heavily on engaging with the people a service is intended to benefit throughout the process. For states interested in engaging with the communities they serve, human-centered design and agile development are well-suited to decrease the barriers to involving the public when building state technology projects.

Let’s start by defining these practices. Human-centered design is a design framework that relies on continuous user feedback to build products and services that work for the people who use them. It allows teams to build an explicit understanding of users, involve them throughout the development process, test and iterate frequently, and address the whole user experience of a product or service.

Meanwhile, agile development is a collection of project management and software development practices that shortens feedback loops and relies on constant feedback, iteration, and collaboration. It can improve products and help teams quickly, safely, and cost-effectively build software that meets people’s needs. Agile development’s emphasis on quick and constant feedback loops allows users to participate in the design of a new service without a major time commitment.

Finally, community engagement refers to a loose set of practices that prioritize working closely with and soliciting feedback from the public in order to build services that truly meet people’s needs. One form of community engagement called co-governance involves creating a positive feedback loop between the public and decision makers that generates trust, creates lasting structures, and builds flexible relationships between institutions and communities.

But it can be challenging for state agencies to spend the time and funds to solicit meaningful public feedback. Legislatively mandated timelines and budgets place pressure on state agencies to implement technology projects quickly. This provides further incentive to limit decision-making and input to internal stakeholders rather than involve the public. Moreover, states’ technology projects often must comply with new laws, be responsive to emergencies, or address newly identified cybersecurity risks or legacy system vulnerabilities.

At the onset of COVID-19, for example, federal lawmakers passed legislation to provide additional grocery benefits known as Pandemic-EBT to families to make up for the meals students would miss while schools were closed in the spring of 2020. In a matter of months, states had to figure out how to operationalize the new benefit program and communicate with families about their eligibility. In this instance, the immediate need required states to prioritize quick action, limiting their ability to solicit public feedback on the program.

Of course, there are ways that state agencies—and other public-oriented organizations—gather public comment. Public forums can be a quick way to get feedback on a policy issue or project. And although public forums are an important facet of inviting community input, they also have drawbacks. Public forums are often hosted after needs are defined and initial solutions drafted, leaving community members to passively listen or give feedback. This limits public input during earlier planning stages, and it makes it difficult to continuously get feedback on ongoing projects.

Should these factors prevent government agencies from obtaining meaningful community feedback, it could widen the disconnect between lawmakers and the public. According to the most recent Edelman Trust Barometer survey, only 43 percent of Americans trust the government “to do what is right.” In order to build public confidence in government, policy makers and technologists must get creative with how they solicit public input. Agile development and human-centered design are great ways to start.

Co-governance as a model for community engagement practices

Co-governance—a specific form of community engagement that involves the public at every level of decision-making—has gained popularity over the last several decades in local government. Its approach to community engagement complements some human-centered design and agile development practices.

Co-governance is built on three core principles, as defined by Hollie Russon Gilman and Mark Schmitt in Building Public Trust Through Collaborative Governance, published in the Stanford Social Innovation Review:

Grant people an authentic seat at the table and imbue the public with actual decision-making power

Follow through on allocating resources

Promote a long-term vision, building momentum and relationships that outlast one-time policy wins

Co-governance encourages institutions to move beyond more passive forms of working with the public, such as listening sessions or town halls hosted after key policy decisions have already been made. It encourages them to stop thinking of public input as just another hurdle to step past, or to reduce community participation to select individuals who serve as tokens rather than groups who can offer a shared vision of their needs.

“Those in power cannot view community engagement as simply a box they must check; instead of window dressing public participation, they must work on mechanisms for genuine participatory control by residents,” write Gilman and Schmitt.

Examples of co-governance range from resident-driven zoning decisions—like those made by Chicago’s Community-Driven Zoning and Development (CDZD)—to youth organizers advocating for school safety reform, like Leaders Igniting Transformation’s (LIT) advocacy in Milwaukee. However, less documentation, if any, exists on the implementation of co-governance practices in civic tech.

At Nava, we are intrigued and inspired by co-governance practices. And though we’re by no means experts on co-governance—a deeply nuanced and complicated framework—we believe that some of the principles of co-governance can be applied to human-centered design and agile development. Through modern, human-centered technology practices, we envision a world where a co-governance framework can be applied at the state and federal levels of government.

Certain tenets of co-governance—namely involving users throughout the process and partnering with organizations that have relationships with the community—are also important facets of human-centered design and agile development. Though co-governance shouldn’t be conflated with these practices, it can inform how teams approach involving users in government technology projects.

Local advocates can help build relationships with communities

It’s a common co-governance practice to partner with local agencies and organizations that are led by and already have existing relationships with the community. By partnering with local organizations, government agencies can establish a baseline level of trust with community members, and they can more easily find participants to give feedback on new projects.

We used this approach when working with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to develop the state’s first-ever paid family and medical leave (PFML) program, which guarantees paid time away from work to care for a new baby, a sick loved one, or one’s own illness. The team partnered with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health to gather data on the utilization and underutilization of PFML benefits. This helped us identify communities that were underutilizing PFML—such as low-income workers and non-gestational partners and fathers—and better understand how to build trust with these users.

Our partners at the Massachusetts Department of Paid Family and Medical leave introduced us to community advocates with connections to underserved communities. Traditionally, community advocates have reasons to be skeptical of external contractors—some may cut corners for the sake of fast-tracking a project, or may not take stakeholders’ needs and input into consideration. Therefore, it was crucial for us to share frequent updates on our work and maintain complete transparency in order to build trust.

Once we built a rapport with advocates, they connected us with members of their communities. We’re now interviewing these people to better understand the barriers they face accessing PFML benefits. We’ll use our findings to tailor our approach and continue iterating on the program we built.

Since we launched in January 2021, the program has paid out $1 billion in benefits to people experiencing major life events.

Leveraging user input to build an unemployment claims tracker

Co-governance emphasizes the importance of gathering individual and group input throughout the process of building a program, not just at the end. This allows policymakers and technologists to develop a holistic and nuanced understanding of the public’s needs and to identify and fix issues early on.

Gathering constant user feedback is also a core tenet of agile development and human-centered design. It allows us to iterate frequently based on users’ needs and to fix bugs and issues early on.

Relying on constant user feedback, we partnered with the state of California’s Employment Development Department (EDD) during the COVID-19 pandemic to rapidly build a system and web application for people to confirm their employment status for unemployment benefits after filing their claim. Applying user research, real-time web analytics, and an agile workflow, we launched an easy-to-use and secure application in six weeks.

On day one, the team collected and distilled input from users and EDD staff to create a working prototype. Then, we quickly screened, recruited, and scheduled a diverse group of eight research participants from 225 volunteers. We employed task-based usability testing to directly observe and learn from how people responded to the application prototype. In task-based usability testing, participants are given common task scenarios and asked to use the prototype to complete them so teams can understand how users experience a digital product.

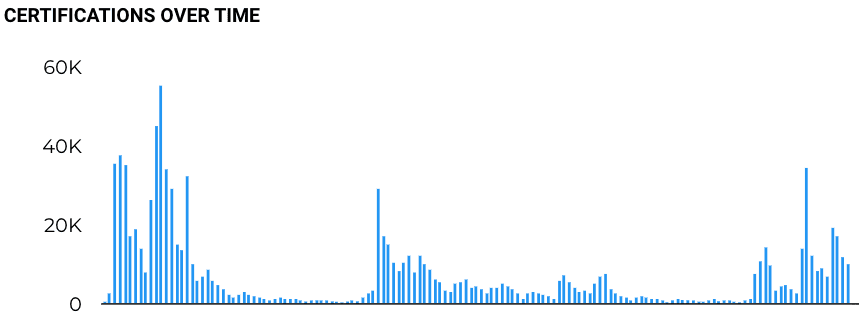

Among other findings, we learned that claimants weren’t sure they could trust the new app because the notifications system didn’t use the SMS text message notifications they were familiar with. In response, we ensured that the app sent reminder messages by SMS text, resulting in an uptick in traffic to the application and completed certifications.

Certification upticks directly correlated to reminders from the EDD communications system.

In this instance, our community engagement efforts helped us get essential information about unemployment insurance to those who need it most. In the first three weeks after launch, there were over 5 million unique pageviews to the California claims status tracker.

Finding a broad range of users: practices for success

When it comes to technology-driven public services, human-centered design methodologies can support a state’s broader community engagement efforts throughout the policymaking and implementation process. Here are some strategies for success:

Compensate people for their time when they participate in user research: People who agree to give valuable time and input to help you meet your research goals should be compensated like any consultant or team member. Build incentives into your budget from the start and determine what compensation policies are already in place. It’s also important to evaluate whether payment forms create an undue burden on research participants. For example, issuing checks might be burdensome to those without a bank account, or auditing may be required for cash or gift card payments. If your agency can’t distribute incentives, consider adding incentive management to your vendor requirements during procurement.

Leverage what you already know to reduce the survey burden carried by specific communities: The populations you want to research might have already gone through this process with a different entity, and being asked to do it again is burdensome. Review whether other agencies or departments in your organization have already conducted relevant satisfaction surveys, landscape assessments, or user research.

Partner with local agencies and organizations that have established relationships with the people you want to reach: Reach out to organizations that are led by and have trusted relationships with the communities you’re looking to serve to ask them to help you recruit individuals from their networks. When reaching out to local organizations, be prepared to describe how you will gather informed consent and integrate individuals’ feedback into your project. If you find you need to conduct outreach to more potential users, develop a strategy to deliberately and thoughtfully pursue the widest range of viewpoints and life experiences possible. This will help ensure you’re conducting representative user research. We recommend starting with inclusive sampling for research activities. It’s also crucial to provide community organizations with something in return. When you’re developing a research plan, ask the community organizations what relevant questions and/or studies you can incorporate. Then, pay them for their time and provide them with any data you compile that can be useful to their work.

Use a UX research tool: If there are particular groups you’ve not been able to connect with from your work with local organizations, consider additional tools available to help UX researchers recruit, schedule, and pay research participants. At Nava, we use Ethnio to create custom surveys tailored to specific user groups and scenarios. However, it’s important to remember that many people lack the access and/or literacy to complete online surveys. That’s why it’s important to walk people through the survey process and to provide alternative feedback options for those who can’t access a computer.

Human-centered design and agile development processes are just one step

Though human-centered design and agile development processes are essential to building user-centered public services, true community engagement means giving people the power to define their community’s priorities and influence how resources are allocated. One way to achieve this is to ensure that the people who will use your technology are part of the process of defining your goals and making decisions about the procurement process, whether it be developing a Request for Information and/or including community representatives on the procurement interview panel.

Bringing a co-governance framework into building public services is achievable and efficient through the use of community engagement practices. By involving these communities from the start and developing a rapport with local advocates, those building services can ensure they better meet user needs and bolster the public’s trust in institutions.

Written by

Senior policy strategist

Director of partnerships and advocacy

Senior Editorial manager